🇮🇹 Nicolai Lilin: un siberiano in Italia

“Chi vuole troppo è un pazzo, perché un uomo non può possedere più di quello che il suo cuore riesce ad amare.”

(Nicolai Lilin)

Chi è Nicolai Lilin?

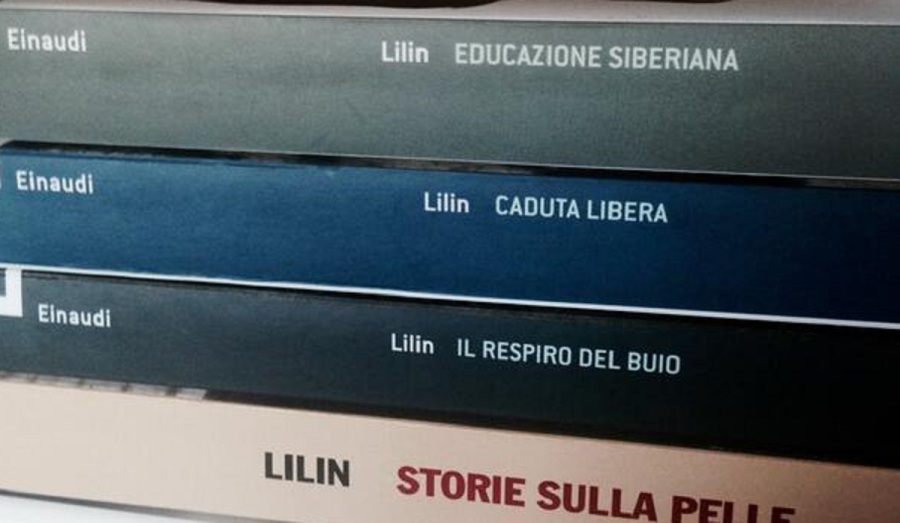

Nicolai è lo scrittore del bestseller Educazione siberiana, di Caduta Libera, Storie sulla pelle e altre opere. Qualche giorno fa ho avuto il piacere di intervistarlo e le domande che gli ho posto, in maggiore o minore misura, potrebbero riguardare tutti noi. Sappiamo infatti quanto sia difficile, nella vita di tutti i giorni, riuscire a trovare un equilibrio prima con sé stessi e poi col mondo che ci circonda e ancora di più, comunicare ciò che proviamo o pensiamo. Quello di cui abbiamo più bisogno sono sicuramente esempi e non soltanto parole; Nicolai, posso dire in tutta onestà, rappresenta proprio una di quelle rare persone che sono riuscite a unire queste due componenti. Infatti, non si può parlare di Nicolai Lilin senza fare riferimento ai suoi scritti e allo stesso modo, non si possono leggere i suoi libri senza pensare alla sua vita rocambolesca. La sua scrittura diventa strumento, o addirittura fede come lui stesso l’ha definita, per esprimere i recessi più nascosti della nostra anima.

La scrittura e il desiderio di comunicare

Nicolai non avrebbe mai sospettato di diventare uno scrittore. La sua famiglia e sicuramente il contesto culturale russo hanno favorito questa sua propensione a leggere e a scrivere, già da quando aveva cinque anni. Però, dall’essere un bambino interessato al diventare uno scrittore molto apprezzato ne è passato di tempo. La sua famiglia, come lui stesso l’ha definita, era “strana” e ruotava attorno alla figura del nonno. Quest’ultimo, criminale siberiano e incarnazione della tradizione, diffidava della politica, dei media e in generale di tutta quella cultura legata al potere che era considerata bassa. Per questa ragione la lettura, che gli ha permesso di arrivare ai classici russi molto presto, rappresentava l’unico strumento di ribellione a uno stato di cose ritenuto corrotto. Nicolai, oltre alla lettura, sente fin da subito il bisogno di tenere un diario in cui scrivere i propri pensieri. Da questo scenario iniziamo già a farci un’idea di quale sia il significato più profondo per lui del leggere, dello scrivere e quindi della cultura.

Però, la vera svolta, quella da scrittore, avviene molti anni più tardi, quando già era in Italia e precisamente all’età di ventinove anni. Collaborava con un’associazione culturale che si occupava di teatro, partecipando in un’occasione alla stesura di una drammaturgia per uno spettacolo sulla Guerra Moderna. Nicolai ne sapeva fin troppo e non per niente uno dei drammaturghi, leggendo dei suoi scritti di approfondimento su questo tema, rimase colpito dal suo modo di scrivere. Così, viene incentivato non solo a coltivare questo talento, ma anche caldamente invitato a mostrare i suoi lavori. Nicolai inizialmente non prestò molta attenzione a questi consigli. Fu solo grazie a un suo amico che presentò, a sua insaputa, dei suoi scritti a degli editori, che iniziò la sua parabola da scrittore con la S maiuscola. Infatti, dopo poco fu contattato da Einaudi che gli propose un contratto decennale, credendo nelle sue potenzialità. Quindi, Nicolai lo si può considerare a tutti gli effetti uno scrittore per caso. Oggi, la scrittura per lui è qualcosa di totalizzante: un piacere, un lavoro, ma soprattutto una forma di vita che lo ha abituato a mettere nero su bianco anche solo pochi pensieri ogni giorno.

Gli scrittori di ispirazione

“Nella lettura è importante analizzare ciò che è stato letto, bisogna svolgere un lavoro di profonda psicanalisi.” Questa sua affermazione dal tono lapidario, può farci comprendere le ragioni profonde che muovono il lettore e che ispirano lo scrittore. Prima di scrivere bisogna sentire, provare determinati sentimenti. Fra i suoi tanto amati mentori spicca fra tutti Gogol’, considerato il padre della letteratura russa, colui che ha dato dimensione e forma al romanzo russo: tutti gli altri hanno seguito le sue orme. Però, puntualizza Nicolai, non per imitare o copiare quel particolare modo di scrivere, ma perché lo stesso scrivere russo è basato sulla dimensione in cui viviamo, sul rapporto più immediato con la vita, con la politica e con la cultura. Tuttavia, ammette di dover molto anche a certi scrittori italiani fra i quali Manzoni e anche Mario Rigoni Stern che ammira soprattutto per la vicinanza, forse emotiva, agli episodi di guerra narrati sul fronte russo durante la Seconda Guerra Mondiale. Dai suoi discorsi si può comprendere come il rapporto fra il proprio modo di scrivere e i modelli a cui si fa riferimento sia sempre una questione di sensibilità, o comunque di affinità.

L’esperienza della guerra

Nicolai conosce questa triste signora, la guerra, molto presto; prima assistendo, quando ancora aveva dodici anni, agli orrori dei disordini seguiti al crollo dell’Unione Sovietica e poi da soldato, combattendo nelle guerre intraprese in Cecenia dalla Russia postsovietica. Dunque, la sua infanzia non è stata delle più facili e lui, come i suoi amici di strada, era dovuto diventare un adulto, però nei panni di un bambino.

La figura che sicuramente ha svolto un ruolo catalizzatore in questi primi anni della sua vita è stato ancora una volta suo nonno, sciamano siberiano, cecchino nella Grande Guerra Patriottica (è così che i russi chiamano la Seconda Guerra Mondiale), e suo maestro di vita che tante volte lo aveva portato con sé in Siberia. Nicolai deve molto a questa persona, perché ha potuto conoscere e riconoscersi in questa cultura che pratica tuttora un cristianesimo paganeggiante, in cui la tradizionale figura del Santo,oltre ad avere qualità spirituali, viene investita di un’aura guerriera. Quindi da un lato viene praticato il culto cristiano, ma dall’altro sopravvive la componente pagana legata al sangue, al rito di uccisione e al concetto fondativo del bene che si oppone al male.

Nicolai mi raccontava divertito che suo nonno pensava che se Cristo fosse esistito ai nostri tempi, pieni di prepotenza, di prevaricazioni e lotta fra classi, sarebbe stato un criminale proprio come lui. La violenza in certe circostanze prima di essere qualcosa di provocato sembra addirittura necessaria. Questo sostrato di credenze e culti siberiani che sono arrivati a lui attraverso il nonno, hanno forse fornito una magra giustificazione ai dolori di questa prima parte della sua vita: prima in Transnistria, sua regione di appartenenza, e poi anni dopo in Cecenia. La vita da soldato è dura, molto più di quella da civili. Corpi dilaniati, devastazioni e violenze, la guerra, come dice Nicolai, è un fallimento che continua ad accompagnare la nostra civiltà: è una pietra che cadendo trascina con sé tutte le altre. Credo che spesso nonostante si ripeta, certe volte forse con troppa retorica, che la guerra sia qualcosa di disumano senza un reale motivo di esistere, si dimentichi la sua reale tragicità. Nicolai per questa ragione difende il proprio vissuto e sostiene che semmai ci fosse da fare guerra a qualcuno, quella sarebbe l’ingiustizia e la divisione favorita da alcune categorie della nostra società. Alla fine, conclude dicendo che i giovani non dovrebbero prendere parte a certi eventi, ma impegnarsi piuttosto nella cultura e nella trasmissione di questa.

Il rapporto tra Russia e Italia

Nicolai sostiene che per quanto riguarda i rapporti fra i due paesi non sussistano semplicemente attenzioni di cortesia o di buon vicinato, ma motivazioni ben più complesse che affondano le proprie radici nella nascita della stessa cultura russa. Bisogna infatti aprire la mente ed essere più consapevoli del fatto che il mondo non sia poi così grande come invece certi modi di fare politica ci vorrebbero far pensare. Le disposizioni in Russia, come tutti sanno, partono da Mosca e in particolare dal Cremlino. Pochi sanno però che la torre campanaria di quest’ultimo e non solo, ma anche tanti altri edifici furono progettati da architetti italiani come Aristotile Fioravanti, Marco Ruffo e Pietro Antonio Solari. Sempre gl’italiani hanno insegnato ai russi a coniare le monete o a costruire i cannoni. Insomma, la grande Russia è nata dagli insegnamenti di architetti, artisti e ingegneri italiani. Stiamo quindi parlando di un’affinità, di una fratellanza che è fondata sulla cultura che Nicolai definisce soggetto vivo che ha reso in fin dei conti la Russia una “creatura” dell’Italia.

Questo genere di rapporto che lascia da parte qualsiasi discorso pieno di buonismi, mostra al contrario una reale condivisione di prospettive e punti di vista fondati sul bello e la bellezza. Perché i russi, dice Nicolai, amano il bello e sono attratti da quell’estetica densa di significato che per ultimo richiama nuovamente il riflesso dell’Italia. Quando si considera il rapporto fra due compagini sociali, fra popoli e quindi paesi bisogna sempre prendere in considerazione la parte migliore di ognuno di questi e cercare di comprenderne le profonde relazioni. Nicolai si considera, come tanti altri, una persona di cultura ed è per questo portato a leggere tali vicinanze in un’ottica diversa e sicuramente positiva. L’esempio che è balzato subito alla sua attenzione è stato quello degli incendi in Siberia che oltre a essere una fin troppo nota tragedia ecologica, è stata anche il banco di prova per l’intesa che sussiste fra Italia e Russia. Infatti, il nostro paese, contro ogni previsione, ha risposto in un modo che nessun’altra nazione si è sognata di fare, mostrando naturalmente l’importanza, soprattutto di questi tempi, di andare oltre gli sciocchi nazionalismi e ad aprirsi al mondo e alle sue diverse culture.

di Guido Lattuneddu

🇬🇧 Nicolai Lilin: a siberian man in Italy

“But remember it is crazy for a man to want too much. Because a man cannot possess more than his heart can love.”

(Nicolai Lilin)

Who is Nicolai Lilin?

Nicolai is the writer of the bestseller Siberian Education, Free Fall, Storie sulla pelle (Stories on the skin) and other works. A few days ago I had the pleasure of interviewing him and the questions I asked him, to a greater or lesser extent, could concern all of us. We know how difficult it is, in everyday life, to be able to find a balance first with ourselves and then with the world around us and even more, to communicate what we feel or think. What we need the most are surely some exemples and not only words; I can honestly state that Nicolai represents just one of those rare persons who managed to combine these components. In fact, one cannot speak of Nicolai Lilin without referring to his writings and in the same way, one cannot read his books without thinking about his daring life. His writing becomes an instrument, or even faith as he himself defined it, to express the most hidden recesses of our soul.

His writing and his desire to communicate

Nicolai would never have thought of becoming a writer. His family and certainly the Russian cultural context have encouraged his propensity to read and write, since he was five years old. However, some time has passed since he was a child interested in becoming a highly appreciated writer. His family, as he himself called it, was “strange” and revolved around the figure of his grandfather. This latter, Siberian criminal and embodiment of tradition, distrusted politics, the media and in general all that culture related to power that was considered low. For this reason the reading, which allowed him to get to the Russian classics very early, represented the only tool of rebellion against a state of things deemed corrupt. In addition to reading, Nicolai immediately felt the need to keep a diary in which to write his thoughts. From this scenario we are already starting to get an idea of what the deeper meaning of reading, writing and therefore of culture is for him.

However, the real turning point, that one of a writer, took place many years later, when he was already in Italy and precisely when he was twenty-nine. He collaborated with a cultural association that dealt with theatre, participating, on one occasion, in the drafting of a dramaturgy for a show about the Modern War. Nicolai knew too much about it and it was not for nothing that one of the playwrights, reading his in-depth writings on this topic, was impressed by his way of writing. Thus, he is encouraged not only to cultivate this talent, but he is also warmly invited to show his works. Initially, Nicolai, did not pay much attention to these tips. It was only thanks to a friend of his who presented, without his knowledge, his writings to editors, that he began his parable as a writer with a capital S. In fact, after a short time he was contacted by Einaudi who offered him a ten-year contract, believing in its potential. So, Nicolai can be considered in all respects a writer by chance. Today writing, for him, is something totalizing: a pleasure, a job, but above all a way of life that has accustomed him to putting even a few thoughts on paper every day.

Inspiring writers

“In reading it is important to analyze what has been read, we must carry out a work of profound psychoanalysis.” This lapidary statement of his can make us understand the profound reasons that move the reader and that inspire the writer. Before writing you have to feel certain feelings. Among his beloved mentors stands out among all Gogol ‘, who is considered the father of Russian literature, the one who gave size and shape to the Russian novel: all the others followed his footsteps. However, Nicolai points out, not to imitate or copy that particular way of writing, but because Russian writing itself is based on the dimension in which we live, on the most immediate relationship with life, with politics and with culture. However, he admits that he owes a lot also to certain Italian writers including Manzoni and also Mario Rigoni Stern whom he admires above all for the closeness, perhaps emotional, to the episodes of war narrated on the Russian front during the Second World War. From his speeches one can understand how the relationship between one’s way of writing and the models to which it refers is always a question of sensitivity, or in any case of affinity.

The experience of war

Nicolai knows this sad lady, the war, very soon; first witnessing, when he was still twelve, the horrors of the disorders following the collapse of the Soviet Union and then as a soldier, fighting in the wars waged in Chechnya by post-Soviet Russia. So, his childhood was not the easiest and he, like his street friends, had to become an adult, but in the shoes of a child.

The figure who surely played a catalytic role in these early years of his life was once again his grandfather, Siberian shaman, sniper in the Great Patriotic War (that’s what the Russians call WWII), and his life teacher who had brought him to Siberia so many times. Nicolai owes a lot to this person, because he was able to know and recognize himself in this culture that still practices a pagan Christianity, in which the traditional figure of the Saint, in addition to having spiritual qualities, is invested with a warrior aura. So, on the one hand Christian worship is practiced, but on the other the pagan component linked to blood, the rite of killing and the founding concept of good that opposes evil survives.

Nicolai, amused, told me that his grandfather thought that if Christ had existed in our times, full of arrogance, abuse and class struggle, he would have been a criminal just like him.

Violence in certain circumstances before being something provoked even seems necessary.

This substratum of Siberian beliefs and cults that came to him through his grandfather, perhaps provided a meager justification for the pains of this first part of his life: first in Transnistria, his region of belonging, and then years later in Chechnya. Soldier life is hard, much more than civilian life. Torn bodies, devastation and violence, war, as Nicolai says, is a failure that continues to accompany our civilization: it is a stone that drags all the others with it.

I believe that despite the fact that it is repeated, sometimes perhaps with too much rhetoric, that war is something inhuman without a real reason to exist, we forget its real tragedy.

For this reason, Nicolai defends his own experience and states that if there was any war to be waged on someone, that would be the injustice and the division fostered by some categories of our society. Eventually he concluded by saying that young people should not take part in certain events, but rather engage in the culture and transmission of this.

The relationship between Russia and Italy

Nicolai argues that as far as relations between the two countries are concerned, there are not simply courtesy or good neighbourly attentions, but much more complex reasons that have their roots in the birth of Russian culture itself. In fact, you have to open your mind and be more aware of the fact that the world is not as big as certain ways of doing politics would make us think.

The provisions in Russia, as everyone knows, start from Moscow and in particular from the Kremlin.

Few know, however, that the bell tower of this last and not only, but also many other buildings were designed by Italian architects such as Aristotle, Fioravanti, Marco Ruffo and Pietro Antonio Solari. Italians always taught the Russians to mint coins or build cannons. In short, the great Russia was born from the teachings of Italian architects, artists and engineers.

We are therefore talking about an affinity, a brotherhood that is based on the culture that Nicolai defines as a living subject that has made Russia a “creature” of Italy after all.

This kind of relationship that leaves aside any subject full of goodwill, on the contrary, shows a real sharing of perspectives and points of view based on beauty.

Russians, as Nicolai says, love beauty and are attracted by that aesthetic full of meaning that lastly recalls again the reflection of Italy. When considering the relationship between two social groups, between peoples and therefore countries, one must always take into consideration the best part of each of these and try to understand their deep relationships.

Nicolai considers himself, like so many others, a person of culture and is therefore led to read these proximities in a different and certainly positive perspective. The example that immediately jumped to his attention was that of the fires in Siberia which, in addition of being an all too well-known ecological tragedy, was also the test bench for the agreement that exists between Italy and Russia. In fact, Italy, against all odds, responded in a way that no other nation has dreamed of doing, naturally showing the importance, especially in these times, of going beyond foolish nationalisms and opening up to the world and its different cultures.

Translated by Manuela Salipante